How to Close the Digital Divide:

And Why It Is a Matter of Public Policy!

This is the second of a two-part series on the digital divide. Part one can be found here.

Why is the Digital Divide a matter of public policy? The answer is simple: Since the turn of the new millennium, high-speed Internet access has become crucial to business, education, health and civic life.

Digital access and inclusion are 21st-century social justice and equity issues. Like the electricity grid, railroads, and the Federal Highway System, broadband infrastructure is a necessary public and private good. Because so much of modern life is dependent on being connected, the California has a compelling state interest to ensure that broadband access is available and affordable to everyone.

Recognizing this, the California Legislature has enshrined in statute a goal of 98% broadband access by 2017. Yet California is falling short of that goal, especially in rural areas, where the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) estimates only 43% of rural households have access to reliable broadband service.

While the private sector has connected 70% of the state, that number has leveled off. To bridge the rest of the divide, the public and private sectors must work together.

In part one of this two-part series, I analyzed the data from the 2016 Annual Survey on Broadband Adoption in California conducted by the Field Research Corporation, underscoring that only 70% of Californians have “meaningful”—i.e., not smart phone reliant—broadband at home. In the second part of this series, I will look at why it is in the government and public interest to close the Digital Divide and how this can be achieved.

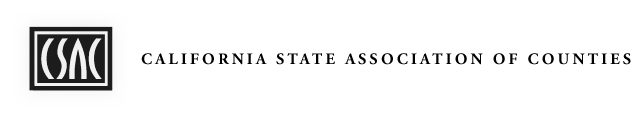

The chart at left from the 2016 Broadband Adoption

Survey shows the top ways Californians use the Internet at home.

The chart at left from the 2016 Broadband Adoption

Survey shows the top ways Californians use the Internet at home.

Three categories are clearly matters of public concern:

1) Education

2) Employment

3) Access to Government

In terms of education, high school students who don’t have meaningful broadband at home face significant challenges completing essays and research papers. In terms of employment, adults without meaningful broadband cannot enroll in online education programs provide opportunities for career advancement.

And citizens of all ages without meaningful broadband cannot access government information and services online.

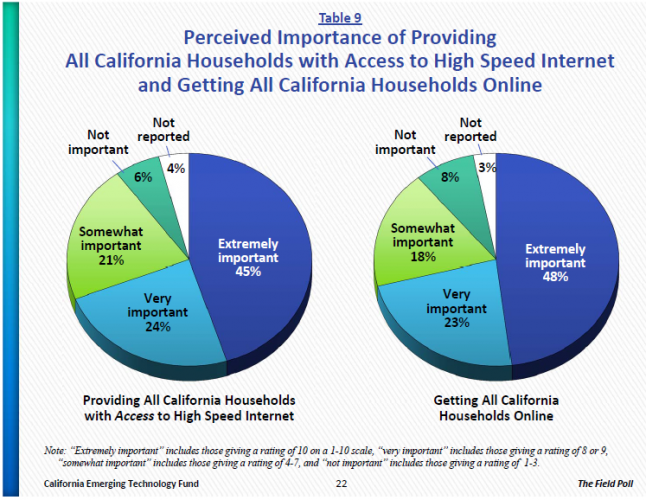

The 2016 Survey on Broadband Adoption found that

Californians view providing all households access to broadband

and getting everyone online as crucial. Less than 10 percent of

respondents said these goals are not important, as the chart at

left shows.

The 2016 Survey on Broadband Adoption found that

Californians view providing all households access to broadband

and getting everyone online as crucial. Less than 10 percent of

respondents said these goals are not important, as the chart at

left shows.

From railroads and the electric grid, to water and the telephone, utilities of all types have history of public funding. Broadband is no different. Over the past 8 years, both the federal and California governments have implemented programs to help increase the deployment of broadband infrastructure.

Under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) in 2009, the federal government provided $7.2 billion in funding for both broadband infrastructure deployment and sustainable adoption programs.

In 2008, the California Advanced Services Fund (CASF) was created by the CPUC as a result of Senate Bill 1193 (Padilla (Stats. 2008, c.393)) to promote the deployment of broadband infrastructure in unserved and underserved areas. CASF has been a strategic and cost-effective resource for helping close the Digital Divide by leveraging pennies per month on phone customers’ bills, to build expensive broadband infrastructure in a huge state of complex terrain. For the CASF deployment projects approved to date, the average cost per household has been $1,363 of which only $441 came from CASF because of available private capital and ARRA funds.

Over the past 7 years, CASF has funded 56 projects to reach over 300,000 households. The largest of those are the CVIN-CENIC and the Digital 395 projects.

The CVIN-CENIC project used $46.6 million of CASF funds, combined with additional funding from the private sector, to offer affordable, middle-mile broadband access. According to Nevada County Connected, the project provided high-speed Internet access to more than 50 community institutions, 160,000 businesses, and as many as 3.6 million people.

The Digital 395 Middle Mile Project is a 10 gigabit, 583-mile fiber optic network connecting San Bernardino County in the south to Mono County in the north. Like the CVIN-CENIC project, Digital 395 is a middle mile project that is providing high-speed Internet access to 36 communities, six Indian reservations, two military bases, 26,000 households and 2,500 businesses—as well as to 35 public safety entities, 47 K-12 schools, 13 libraries, two community colleges, two universities, 15 healthcare facilities and 104 government offices. CASF covered $29,223,432 of the $154 million total project cost, and enabled more than $100 million in federal matching funds.

More recently, on August 28, 2016, CASF approved a $7.6 million grant to fund 70% of a “fiber to the home” project that that will bring broadband to Occidental, California, one of five priority areas in rural Sonoma County.

Despite this record of success, CASF will soon run out of funds. According to publicly available CPUC records, there are currently 14 broadband infrastructure projects, totaling $144 million in the CASF queue awaiting approval. However, there is less than $100 million of available funds remaining. Beyond these pending projects, according to the CPUC’s broadband maps, there are many other unserved and underserved areas that will also need funding for broadband infrastructure deployment funding.

This year, the California Emerging Technology Fund, a public benefit foundation directed by the CPUC to close the state’s Digital Divide, took the lead on reauthorizing CASF to collect additional funds. Through the Internet For All Now Act, CETF has proposed creating a new fund that would collect $50 million per year for 10 years—for total additional funding of $500 million into CASF. (Full disclosure: I am a past CETF board member and currently provide consulting services for the organization on broadband issues.)

Of those funds, $335 million would go toward infrastructure grants. The rest would support:

- community-based organizations that connect low-income households to broadband;

- public housing units where residents lack high-speed Internet access;

- the Broadband Regional Consortia to assist with advocacy and deployment in rural communities;

- the California Telehealth Network to assist both rural and urban communities with access and adoption issues.

The Internet For All Now Act will be reintroduced in the 2017-2018 Legislative session. California’s Counties must ensure passage of this piece of legislation by explaining to their representatives the benefits of connecting all Californians and by holding them accountable for their votes on the issue. Without the reauthorization of CASF, the state will have no plan or mechanism for closing the Digital Divide.

Closing the Divide and ensuring digital inclusion will do much to narrow both the Opportunity Divide and the Income Divide in California. Economic development through broadband is a bipartisan issue. Everybody wants to see more boats rise. Everybody wants to spur individual ability and entrepreneurship. But to get there, we need to foster the right environment. In this case, that environment is ubiquitous broadband infrastructure and universal high-speed Internet access.